When I license an image for commercial use, I know who is licensing the image but I often don't know how they are going to use it, other than web site, book cover, point of sale, etc. And that's ok... I don't really need to know, because the buyer shouldn't have to think about me at all when using the image. But it's always a treat finding my images in the wild. In this case, I happened to find one of my images on the front page of the Southern California Gas Company website.

The Secret Swansea Petroglyphs

There is a secret place near the ghost town of Swansea in the Owens Valley, California, where you can find dozens of ancient petroglyphs dating from as far back as 4,000 years ago. No one knows with certainty who made them. Researchers believe that the petroglyphs at this site were made in several different cycles over a period of a few thousand years. Many generations of petroglyphs have been identified. Early research pointed to the Owens Valley Paiute as the creator of these petroglyphs, but members of the Paiute Tribe maintain that they were created by an earlier people.

The site is unmarked, unprotected; the ancient relics sit alone under the open sky just as they always have. If they knew where to go, people could just hike right to the site. For that reason, its location is a secret; wherever crowds of people go, vandalism and desecration always follow.

I did some sleuthing and had a little luck; Stephanie and I managed to locate the site; I photographed every petroglyph we saw. We felt calmly elated and awed to have found these ancient treasures, and to be able to walk quietly and respectfully alone among them in their atmosphere of ancient ceremonial meaning.

Family Hike

We go hiking a lot, and when we do I often want pictures. But I'm not willing to carry lights or stands or assistants (if I had any) on long hikes and I can't often wait for the light. It's just the camera and maybe a flash and five minutes. But the memories are preserved and the picture-taking moments are fun.

Found Treasure

Often Macro photography is about stopping down the lens to show as much detail as possible. But sometimes you don't want detail; sometimes a smear of color or an overall feeling is what you want. The technical look of a careful macro doesn't cut it. Instead, you want to tell about a feeling. In those cases, you look for light and shape and color, and you open up the lens and just find the patterns.

Lost Treasure

When my wife Stephanie kindly wrote the About Me section of mojavemorning.com, she mentioned my former life as a Forest Service fire lookout. And she was right to include that in the bio, because doing that work more than anything got me energized about photography in a deeply felt, lasting, and almost transcendent way.

Here are some snapshots from those days about a decade ago, when I was working with a compact camera and slowly relearning the craft of photography. Unfortunately, Vetter Mountain Fire Lookout burned to the ground in the massive Station fire in 2009 (I was not on duty at the time). The sadness and irony are not lost on me.

Vetter Mountain Fire Lookout

This is the fire lookout. The structure was built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps and it was administered by the US Forest Service. Because of the ecology and geography of Vetter Mountain, it was one of the few fire lookouts that could be placed on the ground instead of on a tower. From here a person could see about a quarter of the 1,000 square mile Angeles National Forest, from the 10,000 foot high Mount Baldy to the famous Mount Wilson Observatory where astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered the "red shift", proving we live in only one galaxy among millions in a rapidly expanding universe.

Eric and Cooper

In the lookout with my trusty dog Cooper. Cooper was crazy about the forest. It might be hard to see, but at the bottom of the stool in this picture, the legs end in glass insulators. All chairs in the lookout had these… in a lightning storm, the lookout was often the first thing to be struck by lightning. So when I felt the hair standing up on my neck, I got onto one of these chairs in a hurry. There was one harrowing lightning storm I recall in particular, with each bolt of lighting not polite enough to wait until the previous one had finished shattering the air.

Big Tujunga Canyon and fog. The view south from the lookout.

The Osborne Fire Finder

After a lightning storm there was often smoke, and with spotting smoke came the use of this thing. This is the "Osborne fire finder", a neat old antique that still performed its indispensable function. I used it to determine the bearing and distance of any smoke I spotted to accurately radio its location in to the firefighters. Fire lookouts were trained in map reading and orienteering skills, and we had to learn intimately the geography of the forest. We frequently logged weather readings, so we learned about the weather and how to use the weather reading instruments; frequent readings become crucial to firefighters when a fire breaks out. Of course we learned about fire science and since the lookout was open to the public (hikers and mountain bikers would visit on the weekends), we had to be forest docents as well. So we learned about the flora and fauna of the forest, and its history.

Western Diamondback at Vetter Mountain Lookout

Speaking of fauna, we had it. Not just rattlesnakes, but brown bears, deer, marmots, coyotes, mountain lions, little squirrels, birds… lots of lovely animals.

I was really happy. Perhaps I’m not smiling in this picture because I was trying to look official or something. I’m still happy now, but the forest has to continue on without the lookout. It's sad to lose unique old gems like Vetter.

The view North

Chemical Brothers

So I'm shooting at this chemical trench at Bristol Dry Lake in the central Mojave Desert one day when these two dudes see me and mosey over to look at what I am photographing. This is odd in itself. The few people on this minor, desolate desert back road are normally passing through on their way to Joshua Tree or Vegas. But these guys had pulled over to wander around on the empty salt flat.

They peer at me and my tripod and the trench and ask me, "what is this?" and I tell them I guess it's calcium chloride from the dry lake crystallizing out of solution. Or it could be regular table salt. Or it could be they are harvesting chlorine for bleach and pool cleaner. At any rate, it's chemicals they are crystallizing out of solution in the dry desert air.

There is only one way to find out for sure, they decide, and that is to get into the trench and taste the liquid. They start clambering down into the trench. I tell them "dudes, you don't know what that is, and it'll be hard to get back out again". But they are determined to taste the chemicals, to actually put this wild fluorescent green chemical in their mouths.

"Right on", I say, and take their picture. "Put us on Facebook," they call out as they wet their feet and hair in the trench.

The Sky is Not the Limit

The actual edge of the sky, the end of the Earth's atmosphere, is pretty close... only about 62 miles away, depending on how you define the edge. It sort of slowly peters out as you leave the planet, but it's essentially a thin blanket of air we live in. When we say "the sky's the limit", we want to say there are no limits, and that puts us at least well past the sky and out into space.

The most distant thing you can see with the naked eye is called M33. It's a large galaxy in the constellation Triangulum. On a clear moonless night in a very dark place, it resembles a tiny dim smudge of fog in the sky. I've seen it many times, though I don't have any of my own images to show... yet.

So let's push our boundaries out a bit. At only 62 miles, the sky is not the limit. If you want to go naked-eyed and forgo telescopes or cameras, then let's say M33 is the limit. It's around three million light years, (or about 1 followed by 1,200 zeroes miles), away. And as you already know, that means when you see M33, you are actually looking at that galaxy as it was three million years ago. Here on Earth three million years ago, humans did not yet exist. There was only a little ancestor hominid called Australopithecus afarensis who couldn't even make his own tools and loped around not fully erect. So that's old, old light you're seeing.

You can take lovely star pictures with your own dSLR camera. Pick a dry, moonless night. Put your camera on a tripod, use your widest angle lens, go into manual mode, open the aperture up all the way and turn up the ISO as high as you can get away with before the images get too grainy (hopefully that's ISO 3,200 or more). Manually focus on infinity (live view mode can help with this). Leave the shutter open as long as you can.... usually around 30 seconds on most cameras. (If you want to go longer, you may need a cable release for your camera, and the stars will begin to show as streaks due to the rotation of the earth.) Under an autumn sky, M33 will probably even be visible in there.

Above all, experiment in everything you do with your camera! The sky is not even close to the limit if you're willing to try new things.

Taken with the 6D and the 17-40 f/4 L at f/4. 30 seconds.

Taken with the 6D and the Peleng 8mm f/3.5 fisheye at f/4, 30 seconds. This is the entire sky all at once, and the entire 360 degree horizon.

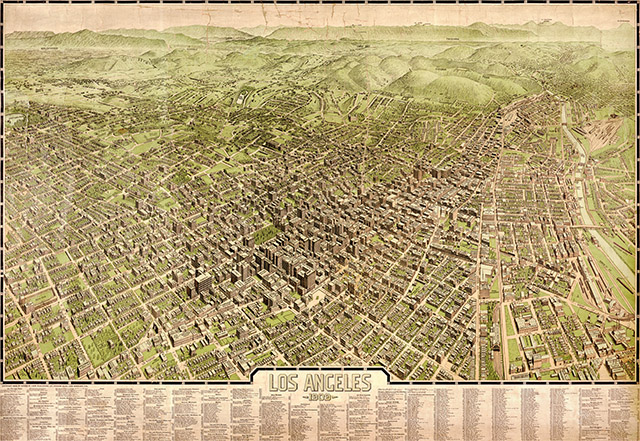

How Are Photos Like Maps?

Photographs and maps have a lot in common in interesting ways. I love both of them dearly, have always loved them, and I want to talk about just one characteristic they share.

A map can't show the real world and all its detail in a 1:1 correspondence. It's impossible. If it could, it wouldn't be a map, it would be reality itself. Reality is of course far too complicated, fluid, and grand to be fully represented by a 2 dimensional static diagram. Instead, a map has to pare down the detail it shows about the world until it becomes simple enough to be useful; one of the most salient features of any map is what isn't there, along with the moment in time the map represents.

So the mapmaker must decide what to show and what to omit. He may have several criteria for the choices he makes, things like utility and elegance and history. He must make something that communicates beautifully without adding confusing clutter, because in including more or less than necessary, the map will begin to fall short of being the very best map of its kind.

Making a photograph is the same. The photographer isn't reproducing exact reality because that's impossible for a photograph. Instead, he interprets, decides what should be included and what should be omitted when he composes the picture. Timing the image can be as important as what's included. The photo itself serves a function, a varying combination of utility and beauty, which are both forms of communication, just as a map is a sort of communication.

How much to include, how much to omit, and when to freeze the moment are design choices for the mapmaker, and aesthetic choices for the photographer. Some of us want to include as much as we can while others attempt a spartan minimalism.

I strive to be a photographer who has a rather different approach from the mapmaker who made the map below: I want to omit as much as I can, and in saying less, communicate more.

1909 Map of Los Angeles

Time to Shine

My wife Stephanie and I were eating on the patio of a restaurant last weekend. (Actually, it was a gourmet sausage restaurant, which is a wee story in itself). I saw her raise her iPhone to take a picture of me. Realizing the setting sun was behind me, I suggested she turn on the phone's little LED flash. It really helped add a sparkle to my eyes (called "catchlights") and fill in dark areas to make the photo more appealing. (If only the camera could have fixed my goofy wind-blown hair!) The photo was finished off by hitting "auto enhance" in the camera app, which is how my tan got so golden, I think.

Most people think of flash as something to use when it's dark out. But on-camera flash often looks terrible when it's dark out. Try using it during the day to fill in shadows... it can really help.

A Different Angle

We went to an event last night with my camera, a soiree for the opening of a public concert series downtown. My favorite shots from the evening didn't show the event at all; they were the ones that treated architecture like landscapes.